So It Goes

Kurt Vonnegut Jr. died last night.

In accordance with good Jewish custom, we will now take advantage of the event of his demise to reflect upon his life and work (because, the rabbis tell us, you can't really know the meaning of a person's life until it's over).

On the other hand, Mr. Vonnegut's biographical details are sufficiently well-know that we need not dwell upon them too much. So briefly:

The man's reputation rests primarily on a series of books he produced in the late 50s and the 60s, particularly The Sirens of Titan (1959), Mother Night (1961), Cat's Cradle (1963), God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965) and Slaughterhouse-Five (1969). They dealt with death, humor, absurdity and madness, and as the Salon Reader's Guide pointed out, it's one of God's mysterious gifts that the man most able in our generation to communicate with us in the spirit of such times was a Nazi prisoner of war and present at the bombing of Dresden.

The five titles mentioned above make a kind of matched set - certain characters appear in more than one of them, their themes and styles are similar, and so on.

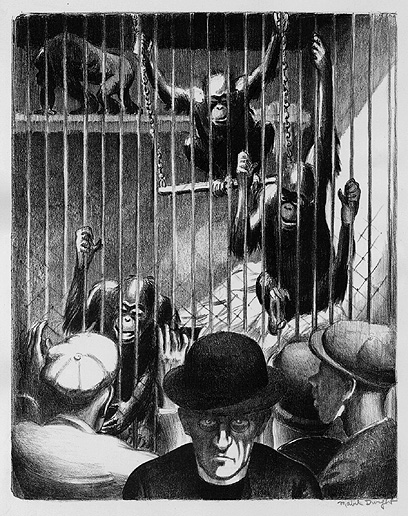

I, personally, have read those classic five novels plus Breakfast of Champions (1973) and Slapstick (1976). I enjoyed them both, as well as his classic short stories "Harrison Bergeron," "Welcome to the Monkey House," and so on, but I'm in no position to comment on the critical consensus that his work after 1969 doesn't match his previous standard.

What does strike me, looking back on Vonnegut's career, is that his courage was unassailable. In particular, he was one of the few non-Jewish artists (Roberto Benigni is another) who ever tried to grapple with the Holocaust, which is all the more remarkable when you consider that his ancestry was German.

He was not so foolish as to set any of his fictions in a concentration camp; instead he used his war experiences to examine the totalitarian mindset, particularly in Mother Night and Slaughterhouse-Five. It was in the introduction to Slaughterhouse-Five, by the way, that he laid claim to the kind of brutally honest realism that we always, always need. "If I had been born in Germany," he mused, "I suppose I would have been a Nazi."

That's a scary thought, but it's a whole lot more useful than any dozen speeches by self-righteous moralists decrying somebody else's sins, because somebody like Vonnegut in his admission of human weakness gives us all permission to be frank about ourselves, too. We might kneel before the aforesaid self-righteous moralist and loudly proclaim "Yes, I'm a sinner!", but what difference will that make in our lives when we leave the house of confession? We read Vonnegut, on the other hand, and was can quietly say to ourselves "Yeah, me too. Now what am I going to do about it?"

Speaking of Vonnegut's courage, by the way - it's a smaller thing, but he also managed to publish a short story called "The Big Space Fuck" in Harlan Ellison's Again, Dangerous Visions. Submitting something with that title to Ellison probably wasn't so very dangerous, but it's still pretty impressive. And I can't think of too many other writers who would have the chutzpah to open a novel with "Call me Jonah" - that a direct cop from Moby Dick, in case you didn't know. (Well, actually, I can think of plenty of writers with that kind of chutzpah, but very few who could get away with it.)

managed to publish a short story called "The Big Space Fuck" in Harlan Ellison's Again, Dangerous Visions. Submitting something with that title to Ellison probably wasn't so very dangerous, but it's still pretty impressive. And I can't think of too many other writers who would have the chutzpah to open a novel with "Call me Jonah" - that a direct cop from Moby Dick, in case you didn't know. (Well, actually, I can think of plenty of writers with that kind of chutzpah, but very few who could get away with it.)

In any case, I'd just like to point something out regarding Vonnegut's date of death. In Jewish life, we are now in the middle of a period called Sefira, the weeks between Passover and Shavuot, between the exodus from Egypt and the receiving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai, and we are commanded in Torah to count each of those days. The rabbis teach us that each of those 49 days focuses on a certain combination of seven of God's attributes - lovingkindness, discipline, beauty, victory, glory, eternity and majesty. The first day focuses on the lovingkindness of lovingkindness, the next on the discipline of lovingkindness, and so on.

Well, last night, when Vonnegut died, we focused on the discipline of discipline, and asked ourselves: In life, do we administer discipline to ourselves and our loved ones in a disciplined manner? Do we discipline in a measured fashion, or do we insist on rules for their own sake?

It's satisfying to know that Vonnegut, who confronted fascism so steadily in his writing by confronting it in himself and who clearly disciplined himself and others with some compassion for their humanity, closed out his life on the day dedicated to that very thing.

Benshlomo says, Good night Kurt Vonnegut, and long live Kilgore Trout.

In accordance with good Jewish custom, we will now take advantage of the event of his demise to reflect upon his life and work (because, the rabbis tell us, you can't really know the meaning of a person's life until it's over).

On the other hand, Mr. Vonnegut's biographical details are sufficiently well-know that we need not dwell upon them too much. So briefly:

The man's reputation rests primarily on a series of books he produced in the late 50s and the 60s, particularly The Sirens of Titan (1959), Mother Night (1961), Cat's Cradle (1963), God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965) and Slaughterhouse-Five (1969). They dealt with death, humor, absurdity and madness, and as the Salon Reader's Guide pointed out, it's one of God's mysterious gifts that the man most able in our generation to communicate with us in the spirit of such times was a Nazi prisoner of war and present at the bombing of Dresden.

The five titles mentioned above make a kind of matched set - certain characters appear in more than one of them, their themes and styles are similar, and so on.

I, personally, have read those classic five novels plus Breakfast of Champions (1973) and Slapstick (1976). I enjoyed them both, as well as his classic short stories "Harrison Bergeron," "Welcome to the Monkey House," and so on, but I'm in no position to comment on the critical consensus that his work after 1969 doesn't match his previous standard.

What does strike me, looking back on Vonnegut's career, is that his courage was unassailable. In particular, he was one of the few non-Jewish artists (Roberto Benigni is another) who ever tried to grapple with the Holocaust, which is all the more remarkable when you consider that his ancestry was German.

He was not so foolish as to set any of his fictions in a concentration camp; instead he used his war experiences to examine the totalitarian mindset, particularly in Mother Night and Slaughterhouse-Five. It was in the introduction to Slaughterhouse-Five, by the way, that he laid claim to the kind of brutally honest realism that we always, always need. "If I had been born in Germany," he mused, "I suppose I would have been a Nazi."

That's a scary thought, but it's a whole lot more useful than any dozen speeches by self-righteous moralists decrying somebody else's sins, because somebody like Vonnegut in his admission of human weakness gives us all permission to be frank about ourselves, too. We might kneel before the aforesaid self-righteous moralist and loudly proclaim "Yes, I'm a sinner!", but what difference will that make in our lives when we leave the house of confession? We read Vonnegut, on the other hand, and was can quietly say to ourselves "Yeah, me too. Now what am I going to do about it?"

Speaking of Vonnegut's courage, by the way - it's a smaller thing, but he also

managed to publish a short story called "The Big Space Fuck" in Harlan Ellison's Again, Dangerous Visions. Submitting something with that title to Ellison probably wasn't so very dangerous, but it's still pretty impressive. And I can't think of too many other writers who would have the chutzpah to open a novel with "Call me Jonah" - that a direct cop from Moby Dick, in case you didn't know. (Well, actually, I can think of plenty of writers with that kind of chutzpah, but very few who could get away with it.)

managed to publish a short story called "The Big Space Fuck" in Harlan Ellison's Again, Dangerous Visions. Submitting something with that title to Ellison probably wasn't so very dangerous, but it's still pretty impressive. And I can't think of too many other writers who would have the chutzpah to open a novel with "Call me Jonah" - that a direct cop from Moby Dick, in case you didn't know. (Well, actually, I can think of plenty of writers with that kind of chutzpah, but very few who could get away with it.)

In any case, I'd just like to point something out regarding Vonnegut's date of death. In Jewish life, we are now in the middle of a period called Sefira, the weeks between Passover and Shavuot, between the exodus from Egypt and the receiving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai, and we are commanded in Torah to count each of those days. The rabbis teach us that each of those 49 days focuses on a certain combination of seven of God's attributes - lovingkindness, discipline, beauty, victory, glory, eternity and majesty. The first day focuses on the lovingkindness of lovingkindness, the next on the discipline of lovingkindness, and so on.

Well, last night, when Vonnegut died, we focused on the discipline of discipline, and asked ourselves: In life, do we administer discipline to ourselves and our loved ones in a disciplined manner? Do we discipline in a measured fashion, or do we insist on rules for their own sake?

It's satisfying to know that Vonnegut, who confronted fascism so steadily in his writing by confronting it in himself and who clearly disciplined himself and others with some compassion for their humanity, closed out his life on the day dedicated to that very thing.

Benshlomo says, Good night Kurt Vonnegut, and long live Kilgore Trout.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home